Editor's note: The Booth Western Art Museum provided source material to Resource Library for the following article. If you have questions or comments regarding the source material, please contact the Booth Western Art Museum directly through either this phone number or web address:

The Indian Gallery of Henry Inman

June 14 - October 7, 2012

While Booth Western

Art Museum's core collection focuses on the West and its people, visitors

often inquire about images of the Native Americans who lived in the Southeast.

To address this interest, Booth Museum opened an exhibition titled The

Indian Gallery of Henry Inman on June 14, 2012.

On view through October 7, 2012, the exhibition features more than a dozen portraits of Southeast American Indian Chiefs from the early 1800s, as well as works by artisans of the time. The exhibition is organized by the High Museum of Art in Atlanta with the support of Ann and Tom Cousins. (right: Henry Inman (1801-1846), after Charles Bird King, Yoholo-Micco(Creek), 1832-1833, Oil on canvas, 30 x 25 inches. High Museum of Art, Atlanta. Anonymous gift 1984.176. Photography by Mike Cortez, Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art, Auburn University)

"With few remnants of the previous tenants who called the Southeast region 'home,' it is easy to forget that by the early 1800s the Cherokee, Creek and Seminole Indians had largely become hybrid peoples, with degrees of assimilation or resistance to European-American customs while preserving their ancient traditions," said Booth Museum Director of Curatorial Services Jeffrey Donaldson. "As we might discover a treasury left by previous inhabitants in our attic, The Indian Gallery of Henry Inman is a time capsule of legendary people who, despite their relocation on the Western frontier, provide an important link between the American South and West."

Portrait artist Henry Inman was hired in the 1830s by Thomas McKenney, former head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, to copy a series of earlier portraits by Charles Bird King. The original portraits by King were done from life, when visiting Indian dignitaries would sit for him. Inman's portraits, which captured the likeness of the Indian delegates, including the cultural influences of the time, were used for a book McKenney and James Hall published, the History of the Indian Tribes of North America. In time, Inman's copies would become more important as a fire at the Smithsonian Institute in 1865 destroyed nearly all of Kings' original portraits along with a collection of American Indian artifacts McKenney had assembled for display.

In the Booth Museum exhibition, visitors will gain insight into the lives of the last leaders of the Five "Civilized" Tribes, particularly the Cherokee, Creek and Seminole Nations who inhabited the Southeast through paintings and lithographic counterparts published by McKenney and Hall. Also on display will be period maps of the Southeast, and original accessories made by Southeastern tribal artisans including embroidered bandolier bags and silver gorgets similar to those worn by the Indian leaders featured in the paintings and lithographs.

In addition to their cultural value as fine art and artifacts, the Cousins collection, particularly the portraits, provide an unparalleled first-hand encounter with the personalities they represent, relaying both gloom and optimism for their diplomatic missions in turbulent times. As a parallel to the portraits, the accompanying artifacts serve not only as objects of beauty or historical documentation, but capture the handiwork and expression of their unknown makers.

Wall text from the exhibition

This exhibition is a modern interpretation of the Indian Galleries of the early 1800s, with a focus on the "Five Civilized Tribes "of the Southeastern U.S., who were relocated to the Western frontier. The first Indian Gallery was created by Thomas McKenney, an officer in the U.S. Department of Indian Affairs under Presidents James Monroe and John Quincy Adams. McKenney documented his negotiations with Native American leaders by collecting artifacts and commissioning portraits of visiting delegates. He brought noted painter Charles Bird King to Washington City, where in his studio, King painted over 100 portraits of visiting Indians. McKenney planned to reproduce these paintings as printed illustrations in a publication on tribes and their leaders. However, when Andrew Jackson became President, his policy of Indian relocation leading Congress to pass the Indian Removal Act of 1830. McKenney was fired by Jackson and lost access to the portraits in the Indian Gallery. As a solution, he hired New York portrait artist Henry Inman to paint a duplicate series of King's originals. Inman's paintings were transferred as drawings on stone, printed, and hand-colored to accompany biographies in the three volume series History of the Indian Tribes of North America. McKenney was so thrilled with the likeness of the lithographs to Inman's paintings that he displayed them side-by-side in a traveling exhibition. Inman's portrait copies became indispensable when nearly all of King's original portraits were destroyed in a fire at the Smithsonian Institution in 1865. Inman's Indian paintings remained in the hands of the last publisher of the History until many of them were acquired by Peabody Museum at Harvard University in the 1880s. The Peabody framed them in "anthropology museum-style" frames until they were sold almost a century later. This exhibition brings a sample of Inman's works to light with a parallel artifact collection.

CHEROKEES

By the early 1800's, the Cherokee people faced an influx of white settlers crossing the Blue Ridge Mountains from the east, forcing them to find hunting grounds further south and west into high country claimed by Georgia. While the tribe became involved in a struggle with the State of Georgia, who wished to remove them, mixed-blood leaders, such as Major Ridge, encouraged adopting the ways of the white man" for survival. Thus, the Cherokee adopted agriculture and a constitutional form of government. On the other hand, by the 1820's, leaders such as Sequoyah and Black Fox, were negotiating with the U.S. to create settlements in the West as an alternative. In 1828, gold was discovered at Dahlonega in Cherokee territory in the East, escalating the conflict with Georgia. Following the Indian Removal Act and Georgia laws restricting Cherokee rights, their leadership asserted their sovereignty in the U.S. Supreme Court. Although Chief Justice Marshall ruled in favor of the Cherokee Nation, the ordeal divided the tribe into the National Party (led by Chief John Ross), determined to delay removal, and the Treaty Party (under Major Ridge), favoring immediate relocation. In 1835, Ridge and others illegally signed the Treaty of New Echota ceding Cherokee lands in the East. President Jackson did not enforce the Supreme Court ruling, thus under his successor, Van Buren, remaining Cherokees were forced on an exodus to the Indian Territory during a harsh winter. Although thousands died on the "Trail Where They Cried," the Cherokee recreated a Nation in the West and endured.

CHOCTAWS and CHICKASAWS

The Choctaw and Chickasaw tribes are historically interconnected, comprising the two westernmost of the "Five Civilized Tribes" of the Southeast to be relocated West. The Choctaw primarily lived in what is now central and southern Mississippi, the Chickasaw in present-day west Tennessee and northern Mississippi. Descendants of the mound-builders, they had led agriculturally-based lifestyles for centuries. Their form of stick ball, a ceremonial contest, was famously captured by Anglo-artist George Catlin. By the early 1800s, white settlers had expanded into their territories, the impetus for a number of cessions , treaties, and visits by tribal delegates to the Federal capital. In the 1820s, Choctaw relations with the U.S. were perhaps best represented by Chief Push-ma-ta-ha. Despite his close ties with the United States, he resisted U.S. Government attempts to coerce Choctaws to cede their traditional homelands. Pushmataha died in 1824, leaving Choctaw leadership to succumb to the U.S. plan that they would be the first of the Southeastern Indian tribes to relocate West by 1833. They exchanged their homelands for a sum of money to compensate for less-desirable farming land in Indian Territory. One Choctaw chief described their relocation as a "trail of tears and death." Similarly, the Chickasaw tribe had had ceded peripheral territories to the U.S., and were confronted with pressure to give-up their traditional lands for what they considered inferior lands in the West. They evaded complete relocation to Indian Territory until 1837 when the U.S. offered them a compensation they considered adequate. They moved west to land leased by the Choctaw in Indian Territory and were never paid by Congress.

CREEKS (Muscogeans)

The term Creek came from the "Indians of Ocheese Creek" (now the Ocmulgee River). They represented a confederation of tribes dominated by the Muscogee (or Muskoghean) people. The Creek are descendants of the mound-builders who created Etowah Indian Mounds. By the early 1800s, Creeks had ceded much of their land to Georgia (and later to Alabama). From the north, the Cherokees had pushed the Creeks to the Chattahoochee River at Standing Peachtree (or "pitch tree") at present-day Atlanta. Many of the Creek leaders represented in this exhibition fought with U.S. allies in the Creek War of 1813-14, defeating the Red Sticks, an anti-white Creek faction. Despite this alliance, incoming white settlers led some U.S. and Georgia politicians to persuade a minority of Creek chiefs to sell remaining Creek lands and relocate in the West. In 1825, part-Scot/Creek Chief William McIntosh, cousin of Georgia Governor Troup, sold most of the remaining Creek lands by signing the Treaty of Indian Springs against the will of his tribesmen. This act prompted a Creek delegation to travel to Washington City (many of them represented here) where they overturned the treaty. Cherokee John Ridge who advised this delegation remarked at how the group was composed of the choice men of their Nation," while John Quincy Adams, while impressed with their attire, also noted their gloomy expressions. Although the delegation regained some Creek lands, the Indian Removal Act of 1830 led to the relocation of most Creeks to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) a few years later.

DESTINY AND LEGACY

Following the Indian Removal Act of 1830, several Midwestern tribes were relocated to the part of Indian Territory that became Kansas, while the Southeastern tribes were removed in phases, called the "Trail of Tears," to a region that is now eastern Oklahoma. While the Five Civilized Tribes faced adaptation to a new land and climate, they soon developed their own educational and political institutions. However, a series of events would once again bring white encroachment into their Nations and cause further dislocation. The 1849 Gold Rush, brought prospectors through their land en-route to California, also attracting Cherokees who had previous mining experience in Georgia. Later, some Indians, especially those holding slaves, supported the Confederacy in the Civil War, causing many black Seminoles to flee to Mexico. After the war, Indian Territory was surrounded by territories emerging as states and became a Wild West refuge for outlaws. By the early 1900s, with the influx of white settlers "The Five Tribes" attempted unsuccessfully to create the Indian State of Sequoyah. Instead, they were absorbed into the new State of Oklahoma in 1907. Meanwhile, in Kansas, the Inman story continued to unfold in an unexpected way. Although Henry Inman never traveled West of the Mississippi River, his son, Henry Inman Jr. became a Colonel in the Army, traveled across the West and wrote books and articles that told stories of the great trails of the frontier West. However, the legacy of his father, the painter Henry Inman, continues with his enduring reputation as "the great chronicler of American Western history." His role, and that of many others in the Indian Gallery story, will not be forgotten.

SEMINOLES

The Seminole primarily originated from Creek Indians or

runaway black slaves in who sought refuge in Spanish Florida. There, they

developed trades such as cattle herding and weaving. As border conflicts

with the U.S. Army increased in the early 1800s, Seminole delegates traveled

to Washington City to negotiate or dispute treaties. During those visits,

their portraits were painted by Charles Bird King. Among these chiefs, Nea-Mathla

played a significant role in provoking the U.S. invasion of Florida led

by Andrew Jackson in 1817. After losing that war, the Seminole were confined

to a reservation in central Florida. In 1825, a delegation of their leaders

went to Washington City to complain about conditions there, only intensifying

pressure from white leaders to relocate them in the West. In 1835, seven

Seminole chiefs including Foke-Luste-Hajo were offered land in Indian Territory

by the U.S. Government. The chiefs agreed to a land exchange, signing the

Treaty of Payne's Landing. In defiance, Seminole leader Osceola launched

a revolt and the Second Seminole War erupted. Although captured, his tactics

inspired subsequent guerilla warriors, Julcee-Mathla and "Billy Bowlegs"

who resisted U.S. troops south into the Everglades. By the 1850s, most of

the tribe had been relocated West. However, after a third war with the U.S.,

a few Seminoles were allowed remain in Florida.

(above: Henry Inman (1801-1846), after Charles Bird King, Tooan Tuhor Spring Frog (Cherokee), 1832-1833, Oil on canvas, 30 x 34 inches. High Museum of Art, Atlanta. Anonymous gift 1984.178)

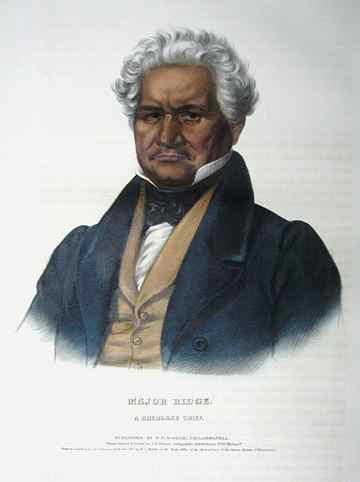

(above: Thomas L. McKenney (1785-1859) and James Hall (1793-1868), after Charles Bird King and Henry Inman, Major Ridge (Cherokee), ca. 1836-1844, Lithograph bookplate. High Museum of Art, Atlanta. Purchase with Charles I. Branan Fund 1984.244)

(above: Thomas L. McKenney (1785-1859) and James Hall (1793-1868), after Charles Bird King and Henry Inman, Detail of Foke-Luste-Hajo (Seminole), ca. 1836-1844, Lithograph bookplate. High Museum of Art, Atlanta. Purchase with Charles I. Branan Fund 1984.240)

Resource Library readers may also enjoy:

Read more articles and essays concerning this institutional source by visiting the sub-index page for the Booth Western Art Museum in Resource Library

Search Resource Library for thousands of articles and essays on American art.

Copyright 2012 Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc., an Arizona nonprofit corporation. All rights reserved.