Editor's note: The Delaware Art Museum provided

source material to Resource Library for the following article. If

you have questions or comments regarding the source material, please contact

the Delaware Art Museum directly through either this phone number or web

address:

"Blessed are the Peacemakers":

Violet Oakley's The Angel of Victory (1941)

February 8 - May 25, 2014

The Delaware Art Museum

is presenting "Blessed are the Peacemakers": Violet Oakley's

The Angel of Victory (1941), from February 8 through May  25, 2014. Oakley's The Angel of Victory, originally

painted for Brooklyn's Floyd Bennett Airfield and now in the Museum's permanent

collections, was the first of her 25 wartime altarpieces, completed just

two weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Thanks to a recent gift from

the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia of over a dozen

preliminary drawings for The Angel of Victory, this exhibition reunites

the altarpiece with its preparatory studies for the first time, allowing

an exciting exploration of Oakley's creative process. (right: Violet

Oakley (1874-1961), The Angel of Victory Triptych, 1941, Oil

on wood panel, 48 x 95 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Joseph Flom

and Martin Horwitz, 1975)

25, 2014. Oakley's The Angel of Victory, originally

painted for Brooklyn's Floyd Bennett Airfield and now in the Museum's permanent

collections, was the first of her 25 wartime altarpieces, completed just

two weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Thanks to a recent gift from

the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia of over a dozen

preliminary drawings for The Angel of Victory, this exhibition reunites

the altarpiece with its preparatory studies for the first time, allowing

an exciting exploration of Oakley's creative process. (right: Violet

Oakley (1874-1961), The Angel of Victory Triptych, 1941, Oil

on wood panel, 48 x 95 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Joseph Flom

and Martin Horwitz, 1975)

"This opportunity to explore the creative process

of an artist whose work is represented in both our American paintings and

Illustration collection is truly remarkable," explains Margaretta Frederick,

Chief Curator at the Delaware Art Museum. "Despite the short amount

of time she was given to complete altarpieces during the war, Oakley made

almost a dozen drawings and oil studies for each of them."

Violet Oakley (1874-1961), one of the first American women

to find fame in the field of public mural painting, in addition to success

as an illustrator and stained glass designer, devoted her 60-year artistic

career to the quest for a just and peaceful world. During World War II,

Oakley joined with the Citizens Committee of the Army and Navy to produce

portable altarpieces for use on American battleships, military bases, and

airfields around the world. The Angel of Victory altarpiece utilizes

scenes from the Christian tradition to instill the American war effort with

universal implications, depicting it as a fight not against other nations

but against the forces of darkness and evil. The artist portrays the American

fight as a sure victory, providing the embattled troops with hope, comfort,

and confidence.

"Blessed are the Peacemakers": Violet Oakley's

The Angel of Victory (1941) was curated by Jeffrey

Richmond Moll, a PhD Candidate in Art History at the University of Delaware

and the Museum's first Alfred Appel, Jr. Curatorial Fellow. This two-month

Fellowship is available for graduate students working towards a museum career.

"As a doctoral student, the Appel Fellowship provided me with an ideal

career opportunity," says Moll. "Through research, gallery layout,

and development of educational materials, it challenged me to do the hard

work of telling the story of Violet Oakley's process and her wartime altarpieces

through the thoughtful selection and arrangement of objects." "Blessed

are the Peacemakers": Violet Oakley's The Angel of Victory (1941) was

organized by the Delaware Art Museum.

About Violet Oakley

Violet Oakley (1874-1961) was born into an artistic family

and found her early efforts at drawing heartily encouraged. She studied

at the Art Students League in New York and in Paris with noted portraitist

of the day, Edmund Aman-Jean. She returned to Philadelphia and and studied

at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and with Howard Pyle at the

Drexel Institute. Pyle's recognition of her sense of color and ability in

composition caused him to push her toward stained glass design and work

in a larger scale than illustration allowed. The artist herself always felt

that Pyle had been one of the two main influences on her work, the other

being the Pre-Raphaelites.

The first and most important commission of Violet Oakley's

career was to design and execute murals for the Governor's Reception Room

in the Capitol Building in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in 1902. She created

nine murals for the Senate Chamber and the 16 murals for the Supreme Court

Room.

Oakley was also sent to Geneva, Switzerland to record the

beginning of the League of Nations in 1927. She exhibited the work from

this trip in prominent locations along the mid-Atlantic coast, including

the Wilmington Society of the Fine Arts. In 1948 Drexel Institute awarded

her an honorary Doctorate of Laws Degree. Violet Oakley continued to work

until the day of her death, February 25, 1961.

The Delaware Art Museum collections now include 53 works

by Violet Oakley representing all facets of her career.

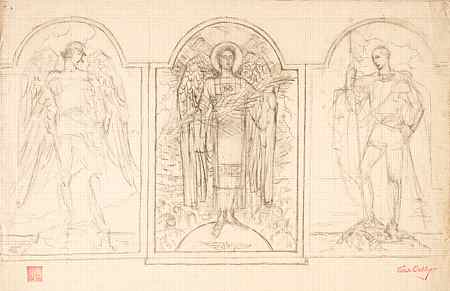

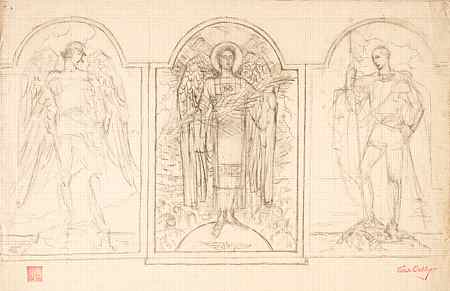

(above: Violet Oakley (1874-1961), Study for The Angel

of Victory Triptych, c. 1941, Charcoal on paper, 16 x 23 1/8

inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine

Arts, Philadelphia, 2012)

-

Wall texts from the exhibition

-

- Introductory text panel

-

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961), one of the first American

women to find fame in the burgeoning field of public mural painting, in

addition to success as an illustrator and stained-glass designer, devoted

her 60-year artistic career to the quest for a just and peaceful world.

Inspired by the Quaker faith, she considered her art to be a vehicle for

social change, believing that beauty could lift up communities and give

rise to a moral society.

-

- During World War II, the elderly Oakley continued this

artistic mission through her work with the Citizens Committee for the Army,

Navy and Air Force. Originally founded to provide leisure materials and

entertainment to boost troop morale, the Committee adopted a new initiative

in the fall of 1941 to produce portable altarpieces for on American battleships,

military bases, and airfields around the world. The Committee hoped that

these triptychs (three-paneled altarpieces) might "carry comfort and

strength to this generation in its overwhelming task of defending the present

and preserving the future."

-

- Oakley's The Angel of Victory Triptych, painted

for Brooklyn's Floyd Bennett Field and now in the Museum's permanent collection,

was one of the earliest triptychs commissioned by the Citizens Committee.

It was the first of 25 wartime altarpieces the artist created for the Committee,

completed just two weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor. This exhibition

reunites the finished painting with preliminary studies for the project

for the first time, allowing an exploration of Oakley's creative process.

Oakley responded to this volatile moment in world history by infusing her

religious work with a democratic spirit echoing her lifelong desire for

peace.

-

- This exhibition is made possible by the Hallie Tybout

Exhibition Fund. Exhibition research funding was provided by the Alfred

Appel, Jr. Curatorial Fellowship.

-

- Additional support is provided by grants from the Delaware

Division of the Arts, a state agency dedicated to nurturing and supporting

the arts in Delaware, in partnership with the National Endowment for the

Arts.

-

-

Didactac panel for "Christ Stilling the Storm"

-

- Triptychs can be set up in a jiffy. And whether it

be in a steaming jungle, or on the rolling deck of a fighting ship, or

in the back of a truck under the fire of guns, there is created an altar?a church.

- Hallowell V. Morgan, Secretary, Philadelphia Triptych

Committee (1944)

-

- "Christmas in Ulithi

Spent in Prayer," showing Oakley's "Christ Stilling the Storm"

during Protestant and Catholic services aboard the USS Massachusetts

- Photograph

- Published in the USS Massachusetts (BB 59) World War

II Cruise Book (194245). Collection of Battleship Cove, Fall River,

Massachusetts

-

- Chaplains Serve in All Theaters of Operation: Protestant

Service in Australia

- Photograph

- Published in The Chaplain Serves: A Narrative and Factual

Report Covering the Activity of the Chaplain Corps (1944). Violet Oakley

Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington,

D.C.

-

- Constructed from lightweight materials (waterproof plywood

for the Army and bullet-proof steel for the Navy), these portable altarpieces

allowed troops to erect a makeshift church anywhere. Chaplains and soldiers

alike recounted how the beauty and churchly appearance of the triptych

could produce a dignified, spiritual atmosphere, which overcame the clamor

and ugliness of war. In the absence of a church or chapel?as seen in the

two photographs above?wherever an altar was, there too was a "church."

-

- Didactac panel for monograms

-

- "The Angel of Victory

Triptych" for Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky (No. 112), by Violet Oakley,

1943

- Photograph

- Citizens Committee for the Army, Navy and Air Force Papers,

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

-

- As Oakley's work with the Citizens Committee continued,

the organization frequently requested that she re-execute old designs for

new patrons. The two drawings at right illustrate Oakley's attempts to

revise her aviator-oriented The Angel of Victory Triptych of 1941

for the army audience at Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky.

-

- Although the 1943 (second) version of The Angel of

Victory Triptych is currently unlocated, a period photograph

(reproduced above) illustrates Oakley's alterations to the original composition.

The constellation of airplanes and the crowd of airmen have been removed

and a large panel adorned with elegant initial letters has been added beneath

the three images. This lettering more clearly identifies both the figures

themselves and the painting's comforting message of victory and peace,

highlighting the words Pax Vobiscum (or "Peace be with you")

at center. These new initials also allude to Oakley's lifelong interest

in the art of the Middle Ages?when illuminated manuscripts featured similarly

elaborate capital letters.

-

-

-

- Didactac panel for triptych

-

- The Angel of Victory Triptych, 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Oil on wood panel

- Gift of Joseph Flom and Martin Horwitz, 1975

- DAM 1975?129

-

- Finished just two weeks after the American declaration

of war, Oakley's first altarpiece nevertheless declares Victory and Peace

to its viewers. While a seemingly paradoxical subject for this historical

moment, it was, in fact, completely in line with Oakley's artistic and

spiritual agenda. The artist received praise at the end of her life for

capturing the triumph of love over hatred, and law and order over a fallen

human race. Her wartime altarpieces likewise show men resurrected, great

conflicts resolved, relationships restored, and a world redeemed.

-

- The Angel of Victory Triptych

utilizes scenes from the Christian tradition to instill the American war

effort with universal implications, depicting it as a fight not against

other nations but against the forces of darkness and evil. This instinct

to transform World War II into a grand spiritual battle might also indicate

Oakley's desire to morally justify the American war effort and thereby

appease her staunch pacifist beliefs.

-

- Oakley's triptych asserts that good will inevitably prevail.

The Archangel Michael and St. George stand firm on either side of the central

scene with sheathed swords, having already defeated their evil foe. The

Angel Gabriel, at center, proclaims "Put Up Thy Sword," heralding

a new era of peace. The artist portrays the American fight as a sure victory,

providing the embattled troops with hope, comfort, and confidence. Oakley's

apocalyptic The Angel of Victory Triptych portrays

an end to global conflict and predicts an ideal world of "Universal

Community."

-

- Didactac panel for war symbolism

-

- Glen Mitchell, Paratrooper Triptych for Fort

Benning Airborne School, Georgia (No. 267)

- Photograph

- Citizens Committee for the Army, Navy and Air Force Papers,

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

-

- Virginia Adams, St. George Triptych for the USS Heywood

(No. 245)

- Photograph

- Citizens Committee for the Army, Navy and Air Force Papers,

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

-

- Edith Emerson, The Archangel Michael Triptych for

the USS Yorktown (No. 376)

- Photograph

- Citizens Committee for the Army, Navy and Air Force Papers,

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

-

- Like Violet Oakley, many artists took up the theme of

warrior saints and angels in their wartime triptychs, revealing the broader

American tendency to see the war in universal, spiritual terms. In one

triptych for the USS Heywood (an attack transport ship that brought American

troops to the Pacific), St. George appears as an ancestral Christian soldier,

standing astride the slain dragon and watching over a battalion of marching

infantrymen. Similarly, in an altarpiece for the Fort Benning Airborne

School, a kneeling, armored angel takes on the guise of a heavenly paratrooper,

as he and his airborne, American compatriot stare off at six parachutes

floating beneath a bright white cross.

Object labels from the exhibition

-

- The Angel of Victory Triptych,

1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Photograph mounted to cardboard

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2013

- DAM 2013?10

-

- Immensely popular in its time, The Angel of Victory

became an emblem of Oakley's late career and of the Citizens Committee

itself. This photograph is probably a proof for the triptych-themed postcards

and Christmas cards that the Committee sold to raise funds for their efforts

during the war.

-

-

-

- Composition Study for The Angel of Victory Triptych, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Graphite and ink on paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?20

-

-

-

- Composition Study for The Angel of Victory Triptych, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Charcoal on paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?16

-

- In her early days studying with illustrator Howard Pyle,

Oakley developed an artistic routine that she followed for the rest of

her career. Exhaustive research for a subject was followed by numerous

study drawings leading up to the finished piece. Despite the short amount

of time she was given to complete altarpieces during the war, Oakley made

almost a dozen drawings for each of them.

-

-

-

- Composition Study for The Angel of Victory Triptych, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Graphite on tracing paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?15

-

- These three sketches demonstrate how Oakley moved from

a rough, initial conception of a work to a more complete composition. Yet,

when compared with the finished triptych, even the most polished drawings

(like the gridded one here) show that the composition was not complete

until the final brushstroke.

-

-

-

- Panel Study for St. George,

c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Tempera and oil on masonite panel

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?31

-

- Immediately upon completion the altarpieces were shipped

to their wartime destinations, before they could be viewed by the public

at home. These large oil studies and the numerous associated drawings allowed

Oakley to display her work on American soil. Oakley exhibited her preparatory

studies frequently, at the annual exhibitions of the Pennsylvania Academy

of Fine Arts, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Corcoran Museum of

Art, in addition to opening her studio regularly. This suggests her work

for the war effort was central to both her personal artistic vision and

her professional aspirations.

-

-

-

- Figure Study for the Angel Gabriel, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Charcoal and white chalk on paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?27

-

- Oakley began her career as an illustrator, and the strong

outlines and flattened features of her figures, like those in The Angel

of Victory or the large panel studies on this wall, reflect trends

in American illustration at this time. Yet, as the carefully rendered studies

for the figure of Gabriel indicate, Oakley was quite skilled at naturalistically

capturing the human form.

-

-

-

- Study for the Angel Gabriel,

c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Charcoal and white chalk on paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?26

-

-

-

- Study for the Angel Gabriel,

c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Charcoal and white chalk on paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?24

-

- Oakley considered careful black and white studies from

live models to be foundational to any painting. She believed that it was

only through numerous sketches that the essence of the figures could be

captured, thereby make a painting accessible to viewers.

-

-

-

- Panel Study for the Angel Gabriel, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Tempera and oil on masonite panel

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?30

-

- In preparing this composition, Oakley searched for biblical

and historical models that would merge the mission of the airmen of Floyd

Bennett Field with that of their heavenly counterparts. The winged warrior

Michael, for example, serves as a timeless emblem for fighter pilots. Smaller

details emphasize the connection between aviators and altarpiece figures.

For instance, the gold designs on Gabriel's heavenly vestments echo the

shape of the airmen's parachute harnesses, and the dove of the Holy Spirit

above Gabriel's head parallels the imagery of the Naval Aviator Badge at

the angel's feet.

-

-

-

- Study for Center Panel of The Angel of Victory Triptych, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Red chalk and graphite on paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?25

-

-

-

- Study for a Pilot, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Brown crayon on paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?23

-

- Oakley greatly admired the 13th-century Italian poet

Dante Alighieri for his ability to fuse eternal themes with contemporary

subjects. This practice was an important aspect of the composition of these

wartime altarpieces, which were part of religious services in distant lands

and makeshift locations. The two sketches at left show Oakley's efforts

to include accurate renderings of American airmen to accompany the sacred

central figures.

-

-

-

- Panel Study for the Archangel Michael, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Tempera and oil on masonite panel

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?29

-

- Oakley used a grid system to expand smaller preparatory

sketches into full-scale studies, called "cartoons." These full-size

sheets, such as the red chalk drawing of the Archangel Michael (at left),

were used to transfer the design onto the wood panels of the altarpiece.

Because the paint was applied very thinly, with the passage of time, one

can often see the corresponding red grid lines beneath the surface of the

final version, as in the case of The Angel of Victory triptych.

(These preparatory grid marks would not have been visible at the time the

painting was completed).

-

-

-

- Cartoon for the Archangel Michael, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Red chalk and charcoal on paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?28

-

-

-

- Monograms for the Archangel Michael and St. George,

Second Angel of Victory Triptych, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Graphite on paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?21

-

-

-

- Victory Monogram and Study for Dedication Text, Second

Angel of Victory Triptych, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Graphite on paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?22

-

-

-

- Text and Composition Study for The Angel of Victory

Triptych, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Ink on paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?17

-

- Initially Oakley chose the Apostle Paul's words at the

end of Romans, Chapter 8 as her inscription for The Angel of Victory,

comparing the American troops to emboldened "conquerors" in a

spiritual army, and their military campaigns abroad to a greater battle

against the forces of evil. As this biblical passage also attests, Oakley

saw the war as one that could not be lost, for, as Paul writes, "neither

death nor life, nor angels nor demons, nor things present nor things to

come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation"

can overcome the power and love of God.

-

-

-

- Text for The Angel of Victory Triptych, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Ink and graphite on paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?18

-

- Oakley eventually selected inscriptions that describe

a heavenly victory over evil achieved by the angels. In her steadfast desire

for peace, she pairs the story of Michael's defeat of "the Dragon"

from Revelation, Chapter 12 with an image of the Archangel sheathing his

sword and standing atop the vanquished beast. Likewise, Gabriel holds out

a "palm of Victory and Peace," referencing the angel's message

in the Gospel of Luke that Christ's birth has brought "peace on earth,

goodwill toward men."

-

-

-

- Study for Text on Left Panel (Archangel Michael) of

The Angel of Victory Triptych, c. 1941

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Ink on paper

- Gift of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia,

2012

- DAM 2012?19

-

- This drawing indicates the careful calculations and textual

changes that Oakley made in order to place the inscriptions around each

of the figures. Note, for instance, the lines and numbers interspersed

throughout this study for the left-hand panel of the Archangel Michael.

Even with such careful preparatory work, however, the drawing marks visible

beneath the surface of the finished altarpiece indicate that Oakley made

alterations in the design right up until completion.

-

-

-

- Study for The Whole Armor of God Triptych, c. 194050

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Graphite on paper

- Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Gift of the Violet Oakley Memorial Foundation

-

-

-

- Study for The Whole Armor of God Triptych, c. 194050

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

- Ink on paper

- Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Gift of the Violet Oakley Memorial Foundation

-

- The armored warriors in these two studies for an unexecuted

altarpiece recall Oakley's depictions of Michael and St. George in The

Angel of Victory Triptych. But, rather than specific biblical or mythological

characters, these figures are purely symbolic. The accompanying text describes

how the soldiers wear "the breastplate of righteousness," "the

shield of faith," and "the helmet of salvation." They fight

"not against flesh and blood, butagainst the rulers of the Darkness

of this World." This theme captures the widespread American belief

that U.S. troops were fighting for a greater cause--the preservation of

"Faith, Family and Freedom."

-

-

-

- The Great Wonder: A Vision of the Apocalypse, c. 1924

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

- Color reproduction

- Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Gift of the Violet Oakley Memorial Foundation

-

- Oakley's interest in the triptych format began long before

World War II. She had an abiding interest in the art and literature of

the Middle Ages and Renaissance art. Her home was filled with curiosities

from her European travels (such as a 14th-century Italian triptych visible

in the photograph at the entrance to this gallery). This color reproduction

of a design for the altarpiece for the Alumni House at Vassar College (1924)

is her first attempt at working in the triptych format and a precursor

to her later altarpieces.

-

-

-

- Composition Study for Christ Stilling the Storm Triptych, 194344

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

-

- Graphite and ink on paper

- Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Gift of the Violet Oakley Memorial Foundation

-

-

-

- Maquette for The Madonna of the Crusaders Triptych, c. 194245

- Violet Oakley (1874-1961)

- Tempera and gold paint on hinged wood panels

- Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Gift of the Violet Oakley Memorial Foundation

-

- Many of the private patrons who funded Oakley's altarpieces

and the military officers who received them visited the artist's studio

to see her progress and even to critique her work. To share these designs

and attract future commissions, Oakley created numerous study drawings

as well as scale models, like this maquette for a larger triptych of The

Madonna of the Crusaders.

-

-

-

- Dedication at Chapel of Philadelphia Navy Yard, with

Violet Oakley and officers in front of her triptych, "Christ the Carpenter,"

December 30, 1945

- Photograph

- Violet Oakley Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian

Institution, Washington, D.C.

-

- Painting triptychs came to be seen as an artist's wartime

obligation as well as a patriotic and spiritual duty. As the photograph

at left suggests, these altarpieces gave artists a symbolic means of joining

the war. Many were dedicated in impressive formal military ceremonies,

like the one pictured here at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, where artists

like Violet Oakley (standing at center) were celebrated for their artistic

contributions to the war effort.

-

Wall quotes from the exhibition

-

- Pure drawing takes no note of color. Correct drawing

is the basis of all painting. Painting is only colored drawing.

- - Violet Oakley, "Questions from the Children,"

Violet Oakley papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution,

Washington D.C., 1926

-

-

- Many of [the altarpieces] will come back as battle

scarred as any veteran or lie with the good ship that bore it at the bottom

of the sea. But all will have served the cause that is the cause of all

of us.

- - H.I. Brock, "Altars of Freedom," New York

Times, October 18, 1942

-

Editor's note: RL readers may also enjoy:

Read more articles and essays concerning this institutional

source by visiting the sub-index page for the Delaware

Art Museum in Resource Library.

Search Resource

Library for thousands of articles and essays on American art.

Copyright 2014 Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc., an Arizona nonprofit corporation. All rights

reserved.

25, 2014. Oakley's The Angel of Victory, originally

painted for Brooklyn's Floyd Bennett Airfield and now in the Museum's permanent

collections, was the first of her 25 wartime altarpieces, completed just

two weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Thanks to a recent gift from

the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia of over a dozen

preliminary drawings for The Angel of Victory, this exhibition reunites

the altarpiece with its preparatory studies for the first time, allowing

an exciting exploration of Oakley's creative process. (right: Violet

Oakley (1874-1961), The Angel of Victory Triptych, 1941, Oil

on wood panel, 48 x 95 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Joseph Flom

and Martin Horwitz, 1975)

25, 2014. Oakley's The Angel of Victory, originally

painted for Brooklyn's Floyd Bennett Airfield and now in the Museum's permanent

collections, was the first of her 25 wartime altarpieces, completed just

two weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Thanks to a recent gift from

the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia of over a dozen

preliminary drawings for The Angel of Victory, this exhibition reunites

the altarpiece with its preparatory studies for the first time, allowing

an exciting exploration of Oakley's creative process. (right: Violet

Oakley (1874-1961), The Angel of Victory Triptych, 1941, Oil

on wood panel, 48 x 95 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Joseph Flom

and Martin Horwitz, 1975)