Editor's note: The

Albany Institute of History and Art provided source material to Resource

Library for the following article or essay. If you have questions or

comments regarding the source material, please contact the Albany Institute

of History and Art directly through either this phone number or web address:

Iroquois Games and Dances:

Paintings by Tom Two Arrows

March 10 - December 31, 2007

The Albany Institute

of History & Art is presenting the exhibition Iroquois Games and

Dances: Paintings by Tom Two Arrows. The exhibition will showcase the

works of Albany artist Thomas J. Dorsey, (1920-1993), also known by his

Indian name Tom Two Arrows.

The documentary nature of these paintings reveals Dorsey's

first-hand knowledge of the subject matter and his interest in presenting

to the viewer the richness and vitality of traditional Iroquois culture.

Commentaries will accompany each of the paintings that clearly show an awareness

of issues of identity and empowerment for native people that remain relevant

today.

At the age of 21, Dorsey, a member of the Delaware (Lenni-Lenapee)

tribe and adopted by the Ondondagas (an Iroquois tribe), was commissioned

by the Albany Institute of History & Art to create a series of paintings

depicting Iroquois games and dances as result of the interest and enthusiasm

of John D. Hatch, Jr. who served as Director from 1940-1948. While working

on this project, Dorsey spent six weeks on the Ondondaga reservation in

Nedrow, near Syracuse, New York.

In 1942, his exhibition Iroquois Games and Dances by

Tom Two Arrows, was shown at the Albany Institute. For the next two

years the exhibition traveled to the California Palace of the Legion of

Honor, San Francisco; Museum of American Indian, New York City; Denver Art

Museum, Southern Plains Indian Museuml Andarko, Olklahoma; and the Rochester

Museum and Science Center under the Auspices of the American Federation

of the Arts.

Rather than showing Iroquois games and dances as relics

of the past, Dorsey argues through his images and text that "the Iroquois,

or as they call themselves, the Haudenosaunee (People of the Longhouse),

are a powerful and sovereign political force in America Today."

Wall text for the exhibition

Iroquois Games and Dances: Paintings by Tom Two Arrows

Albany artist, Thomas J. Dorsey, (1920-1993), is also known

by his Indian name, Tom Two Arrows. At age 21 he was commissioned by the

Albany Institute of History & Art to create a series of paintings depicting

Iroquois games and dances as a result of the interest and enthusiasm of

John D. Hatch, Jr. who served as director from 1940-1948. Dorsey, a member

of the Delaware (Lenni-Lenapee) tribe and adopted by the Onondagas (an Iroquois

tribe), was a graduate of Albany High School where he studied with Herbert

Steinke (1894-1978/79). While working on this project, Dorsey spent six

weeks on the Onondaga reservation in Nedrow, near Syracuse, New York.

The documentary nature of these paintings reveals Dorsey's

first-hand knowledge of the subject matter and his interest in presenting

to the viewer the richness and vitality of traditional Iroquois culture.

Dorsey also wrote commentaries for each of the paintings that clearly show

an awareness of issues of identity and empowerment for native peoples that

remain relevant today. These commentaries have been slightly updated for

this exhibition. Rather than showing Iroquois games and dances as relics

of the past, Dorsey argues through his images and text that "the Iroquois,

or as they call themselves, the Haudenosaunee (People of the Longhouse),

are a powerful and sovereign political force in America Today."

According to art historian, Dr. Roberta Bernstein, in her

essay in 200 Years of Collecting, Dorsey emphasizes the activity

as well as the clothing and objects associated with a specific game or dance

in his compositions. Figures are rendered abstractly without facial features.

Figures and objects are placed against monochrome background, and only minimal

space is indicated through overlapping. His painting style, a savvy blending

of elements from Native American arts and modernist abstraction, features

bright, decorative colors and compositions based on patterning and symmetry.

Included in this exhibition are paintings from the original

series, silk-screened prints and manuscript materials in the center case.

January 19- May 26, 2002

The Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois Confederacy, also known as the Iroquois League,

was first comprised of five tribes or nations: the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga,

Cayuga, and Seneca. In 1722 the Tuscarora joined and the confederacy became

Six Nations. The Iroquois occupied lands in upstate New York, northern Pennsylvania

and across the border in the southern Canadian provinces of Ontario and

Quebec.

Tradition credits the formation of the Confederacy, established

between 1570 and 1600, to Dekanawidah, born a Huron, who is said

to have persuaded Hiawatha, an Onondaga living among the Mohawks, to abandon

cannibalism and advance "peace, civil authority, righteousness, and

the great law" as sanctions.

Cemented mainly by their desire to stand together against

invasion, the tribes united together with a common council composed of clan

and village chiefs; each tribe had one vote and all decisions had to be

unanimous. The joint jurisdiction of fifty chiefs, known as sachems, embraced

all civil affairs at the intertribal level with the main Onondaga village

serving as the meeting place for the Confederacy. After the American Revolution,

United States government leaders used the Iroquois Confederacy as a model

for planning the new democracy. The autonomy of the states was based on

the different Iroquois tribes; the senators and congressmen were like the

fifty sachems; and the capital, Washington, D.C. was similar to the Onondaga

village.

The longhouse, a distinctive elm bark-covered structure

between fifty to one hundred feet long, used in native villages for housing

tribal members, was also the symbol of the Iroquois. Metaphorically speaking,

the longhouse extended across New York State with the Mohawks guarding the

Eastern Door, the Senecas guarding the Western Door and the Onondaga, keepers

of the council fires and the wampum records, in the center.

Before the American Revolution the Iroquois carefully retained

their autonomy by working with the British against the French, but during

the War a split developed between two Iroquois factions. The Oneida and

Tuscarora supported the American cause and the rest, under the leadership

of Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant, supported the British.

In 1784 the Iroquois acknowledged defeat at the Second

Treaty of Fort Stanwix. Ten years later at the Canandaigua Treaty, the Iroquois

and the United States pledged not to disturb the other in lands that had

been relinquished. Of the Six Nations, the Onondaga, Seneca, and Tuscarora

remained in New York, eventually settling on reservations; the Mohawk and

Cayuga withdrew to Canada; and a generation later the Oneida departed for

Wisconsin.

Today, the Iroquois call themselves Haudenosaunee,

or People of the Longhouse. There are about sixty thousand Iroquois in the

United States and Canada. The paintings in this exhibition reveal significant

aspects of Iroquois spirituality and culture.

Thomas Dorsey, Jr. or Tom Two Arrows (1920 -1993)

Thomas Dorsey, Jr. was born in Albany where he resided

for most of his life. In 1942 his exhibition, Iroquois Games and Dances

by Tom Two Arrows, was shown at the Albany Institute of History &

Art. For the next two years the exhibition traveled to the California Palace

of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco; Museum of the American Indian, New

York City; Denver Art Museum, Southern Plains Indian Museum, Andarko, Oklahoma;

and the Rochester Museum and Science Center under the auspices of the American

Federation of the Arts.

In 1942 Dorsey joined the United States Art Corps and was

stationed in North Carolina where he completed murals in the Service Club

on the base depicting scenes of everyday life related to tribes native to

that state. After the war Dorsey designed and executed murals and backgrounds

for exhibits at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City,

including those for "Masks and Men," "Native Fashions"

and "Indians of the Amazon." He created murals for the Consulate

of Pakistan in New York City and for Scandinavian Airlines. In 1970, Dorsey

was commissioned to make a series of paintings for Indian Quadrangle at

the University at Albany, State University of New York. These paintings

done on animal hide pay tribute to the tribes of the Iroquois nation.

Dorsey's work is represented in the permanent collections

of the Museum of the American Indian; Pilbrook Museum of Art and Gilcrease

Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma; Denver Art Museum; American Museum of Natural History;

Montclair Art Museum, Montclair, New Jersey; the University at Albany, State

University of New York and the Albany Institute of History & Art.

Dorsey was the recipient of an "Indian Leadership"

grant from the YMCA Indian Guides to teach traditional Indian painting at

the Onondaga Indian Reservation to students. He lectured on American Indian

arts, crafts and customs in Southeast Asia for the United States Department

of State and taught a course at the University at Albany, State University

of New York on the relationship of the Indian to his environment and the

arts and crafts of the Woodland Indians using natural materials.

During his career Dorsey also illustrated children's books

on American Indians such as Eagle Feather by Clyde Robert Bulla and

Little Boy Navajo by Virginia Kester Smiley. He also did freelance

graphic design and designs for textiles and ceramics.

Iroquois Games and Dances

These paintings depict scenes of traditional life among

the Onondaga of Central New York, one of six Indian nations making up the

political confederacy of the Iroquois of New York State and southern Ontario.

The Onondaga are known as "Keepers of the Council Fire". Their

important roll as peacekeepers and mediators has encouraged the Ononadaga

to maintain a strongly traditional way of life today. The Grand Council

of Chiefs meets on the Onondaga Reservation near Syracuse to discuss policy

and carry on the business of the present day Confederacy. The Iroquois,

or as they call themselves, the Haudenosaunee (People of the Longhouse)

are a powerful and sovereign political force in America today.

Although the style of these paintings appears to present

an old fashion culture long-since disappeared, the fact remains that the

Haudenosaunee still conduct these ceremonies, play these games, perform

these dances, and sing these songs today wearing modern clothes while doing

them. Their languages are used daily and may even be growing, thanks to

educational encouragement on some reservations. Traditional life goes on

behind the scenes away from media attention, although not immune to it.

The Haudenosaunee can be adept at living in today's predominant culture

when they need to, although this often brings them enormous problems. But

they will find their own way to persist, and so the traditions of the Haudenosaunee

will be strengthened in the future.

Most Haudenosaunee ceremonies, held on the reservations

in special buildings called "the Longhouse," are not open to the

public. Followers of the traditional religious rituals wish to remain private,

conducting their special ceremonies only with others sharing their beliefs

and language. Iroquois "socials," on the other hand, feature food,

games and social dancing in a festive rather than ceremonial context. These

activities can be performed for non-Indians.

Tom Two Arrows

1942

-

- GA. NU. NI. DIS. SE. NU-U. NU. GA. NUS or I Come From

Water

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Gouache on composition board, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1942.93.2

-

- The Haudenosaunee creation story tells how the earth

was formed on the back of a giant turtle when the first woman fell through

a hole in the Sky World. She gave birth to a daughter, who became the mother

of the good and evil twins. After defeating the bad twin in a series of

contests, the strong-minded one became the Creator, "Holder of the

Heavens," and formed all the parts and inhabitants of the world. He

created people, who despite his best efforts still bear some of the capacities

of his wicked brother.

-

- As people lived on the earth, they often needed guidance

from the Creator's messengers. One of these was the Peacemaker, who, along

with his translator Hiawatha, brought words of peace to the warring nations

and formed the Iroquois Confederacy. Another man of vision was Ganeodiyo

(Handsome Lake). In the 18th century he help to bring new life to traditional

Haudenosaunee culture by introducing Gai-wiio, or the way

to live a good life. His instructions to men and women are recited at ceremonies

so that traditional people may remember and follow the right path.

-

-

- CA.NAN.DAI.GUA or Treaty

of Canandaigua

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Gouache on composition board, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1942.93.3

-

- Signed in November 1794 by the United States government

and the chiefs of the Iroquois Confederacy, this treaty confirmed the rights

of the Confederacy. It established the precedent of sovereignty so important

to the Haudenosaunee: the six nations of the Confederacy are separate

and equal political entities, joined together in an alliance, comparable

in status to the United States and entitled to treatment as sovereign states.

Nearly six million acres of land held by the Oneida, Onondaga, and Cayuga

were "guaranteed" by this treaty. Also, it defined the boundaries

of Seneca-held lands. The Haudenosaunee value this agreement highly

and commemorate its signing every November with a parade and feast in Canandaigua,

New York.

-

- In the words of Mike Myers, an Onondaga chief:

-

- The Iroquois Confederacy is among the world's oldest

continuously functioning democracies. In 1784 and 1794 our government concluded

treaties with (the U.S) that recognize the political integrity and separateness

of our nations and that grant the U.S. land on which to live. These treaties

formed the political basis of the Indian nations' relationship to the U.S.

But beyond the political reasons for our steadfast refusal to be integrated

are spiritual reasons. It is not a mistake that the Creator of life put

our people on the earth, gave us our language and beliefs, and provided

a model for our political organization that endures to this day.

-

-

- SUH.DI.KUN.YA or Let Us Eat

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Gouache on composition board, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1942.93.4

-

- In a small cookhouse adjacent to the longhouse, women

prepare corn soup, fry bread and meat stews to feed the participants at

festivals and ceremonies. Feasting provides a way for the community to

share the fruits of its labor, while giving the dancers and speakers a

break from their activities.

-

- In the painting, women wear traditional Haudenosaunee

clothing: a printed or plain cotton overdress decorated with white beadwork,

a dark wool skirt also edged with beads and ribbon work, dark wool beaded

leggings and moccasins. Older women wear dark scarves or shawls. The food

is served from a large wooden bowl with a wooden ladle, which is often

carved with an animal clan symbol such as a bear, heron or turtle.

-

-

- WA.HA.DO.WET.TA or Hunting

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Gouache on composition board, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1942.93.5

-

- Traditional Haudenosaunee hunting technology was

ingenious and successful. Not only were deer hunted with the bow and arrow,

but they could also be snared or herded into enclosures. One estimate calculates

that these methods could net up to two thousand deer per season for the

nation. Female animals were not killed native people safeguarded

their food supply for the future.

-

- In addition to deer, all sorts of animals were eaten

in the past including beaver, bear, fish, turtles, and pigeons. The hunting

method depicted in the painting uses a blowgun for shooting down birds.

Usually made of alder wood, the guns could be as long as six feet. Thin

arrow-darts with sharpened points were carried in bark quivers, then blown

out of the stem by a sharply exhaled breath. Up until the late 19th century

these guns were used to discourage robins from eating the ripening fruit

of cherry trees.

-

-

- DA.HOON.GU.GWA.A.GWA or

LaCrosse

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Gouache on composition board, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1942. 93.7

-

- Perhaps the most famous Indian game, lacrosse was first

mentioned by the French in 1662. The distinctive Haudenosaunee racket

was described as "la crosse" because it resembled a bishop's

crozier. The Haudenosaunee believe that lacrosse was first played

between the good and bad-minded twins, as a contest expressing the duality

of human nature.

-

- Even as played today, with boundaries and rules, lacrosse

is a game requiring strength and endurance. In the past, players would

observe special diets and would train carefully for the long, arduous bouts.

The most important part of their preparation would be a statement of thanks

to the Creator for the gift of the game. Often a game would be held to

enhance the power of medicine if a person was sick the loud, exciting

contest between healthy players would attract the Creator's attention.

-

- The early games took place without boundaries, over fields

and sometimes into woods. Team sizes varied, but were always equal. Games

could last for days. The winning team was the one that scored three goals,

by hitting a tree or pole three times.

-

-

- PE.QUA.NOCK or Cleared

Land

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Gouache on composition board, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1942.93.8

-

- Cleared land makes a good place to hold "hoop and

spear" games. The young man wearing the turkey plumes has just rolled

one of the hoops for his companion to pierce with spear.

-

- The Thunder Ceremony, held in April, celebrates the clearing

of land for planting. After the War Dance is performed, the hoop and javelin

game is played as part of the ritual. As well as an entertainment, Haudenosaunee

games represent symbolic contests between the good and dark sides of human

nature. Games also provide a way for opposing clan groups to "let

off steam." Since all political decisions among the Haudenosaunee

must be made unanimously, it becomes important for the society to construct

a mechanism for allowing dissent and friendly disagreement.

-

- Two teams of from fifteen to thirty players station themselves

along a course. One team rolls a wooden ring down the course; the other

team aims its six-foot hickory wood javelins at the moving ring. Players

who hit the ring win the javelins of the other team; the victorious team

is the one winning all the javelins. Sometimes the game is played more

as target practice toward a particular object, or as a long distance toss.

-

-

- GA.WA.TA or Snow Snake

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Gouache on composition board, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1942.93.9

-

- Snow snake is a popular winter game. The players are

dressed in warm winter clothing. After a log has been towed through the

snow, forming a track, the players attempt to send their highly polished

sticks known as "snakes" gliding down the track as far as possible

with the head of the snake in an upright position. "Snakes" can

travel up to one hundred miles an hour, and can seem almost alive as they

glide. "Snakes" are carved from hard, fine-grained wood such

as hickory, maple, ironwood or juneberry. They are polished, carved into

a thickened, rounded tip; soaked in water and sometimes oil, dried, sanded,

then shellaced. At the tip, the shiner or maker pours melted lead into

a slight depression, to provide weight when thrown. These "snakes"

are often found in most homes in the summer, waiting the winter betting

season.

-

- A snow snake maker, called a "shiner,'' knows his

craft like a science and has the ability to modify his treatment of a snake

to suit weather conditions, like a skier with different waxes. From Lewis

H. Morgan's 1851 description: The snake was thrown with the hand by

placing the forefinger against its foot, and supporting it with the thumb

and remaining fingers. It was thus made to run upon the snow crust with

the speed of an arrow, and to a much greater distance, sometimes running

sixty or eighty rods.

-

-

- GOON.WHI.O.DI.IT.SA or

Peach Stone Game

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Gouache on composition board, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1942.93.10

-

- During the Midwinter ceremonies of renewal, held after

the first full moon of the New Year, people play this game as an amusement

to the Creator. The game reenacts one of the contests between the good

twin (Sapling) and the evil twin (Flint) as they struggled for dominance

as the first men on earth. Two opponents take turns hitting a flat-bottomed

wooden bowl against the floor, bouncing six peach stones inside. The stones,

blackened on one side, are counted like dice, depending on how many colored

sides turn up. Friends and relatives of players place bets of their valuables,

and the winner takes all.

-

- The importance of the peach stone game in Haudenosaunee

ritual helps us to understand the Iroquois attitude toward gambling. Games

of chance are considered to be sacred, played only in ceremonies honoring

the Creator. "The message you send back to the Creator is that you

are grateful for what you have and willing to share it with others."

-

-

- GREEN CORN DANCE

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Gouache on composition board, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1942.93.13

-

- The Green Corn festival, held in August, celebrates the

ripening of the staple crops: corn, beans and squash. Called "The

Three Sisters," these plants grew from the body of Skywoman's daughter

after she died giving birth to the good and evil-minded twins. As the "Life

Supporters," corn, beans and squash are honored in this important

ceremony that runs for four days. Four central ritual dances and games

are performed, faithkeepers recite the long Thanksgiving Address and a

feast with social dancing is held.

-

- In this painting a singer beats a turtle rattle against

a wooden bench, providing the rhythm for dancers. The corn design in the

background also appears in many Haudenosaunee decorative arts, such

as beadwork, quillwork and silver.

-

- We give greetings and thanks to the plant life. Within

plants is the force of substance that sustains many life forms among them

are good, medicine and beauty. From the time of creation we have seen the

various forms of plant life work many wonders in areas deep below the many

waters and the highest of mountains. We give greetings and thanks, and

hope that we will continue to see plant life for generations to come. (From the Thanksgiving Address.)

-

-

- GI.EO.A.O.WAN.NA or Partridge

Dance

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Gouache on composition board, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1942.93.13

-

- Also known as the Pigeon Dance, this dance is performing

socially rather than as part of a ritual. It is taken from the mating antics

of the male and female partridge during spring. This male impersonator

is keeping himself aloof from the female as she endeavors to catch his

eye with each coy step. The dance concludes with the female getting her

way and the dancers leaving the space together.

-

- Most Haudenosunee enjoy dancing and participate

regularly, even the littlest children who are carried by their dancing

parents. The most adept and athletic people are the ones who do the difficult

steps of the energetic the War Dance and Smoke Dance.

-

- Greatly honored for their skills, good singers have strong,

melodious voices and know vast repertories of songs for each dance. To

sound the background rhythm, singers shake gourd or horn rattles, or large

rattles made from the hollow body of a turtle with dried corn kernels placed

inside. Turtle rattles can also be struck against the top of the singers'

bench to give the beat.

-

- In this painting the singer plays a water drum, a typical

Haudenosaunee instrument which they call "the little boy."

Made from wood with a skin or hide head, the drum is filled with water

then inverted to keep the head wet. When struck with a small, carved, wooden

beater, the water drum makes a rich hollow sound.

-

- The sense of community and beauty evoked by the music

of a singer, his drum, and the dancers can be very powerful. As the Haudenosaunee

say, "We do not pray - we dance."

-

-

- O-JUN.N-TA.O.WAN.NA or

Fish Dance

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Gouache on composition board, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1942.93.16

-

- Extremely popular, especially with younger Haudenosaunee,

the Fish Dance allows girls to choose their own partners. Here young men

wear their finest beadwork to attract the admiration of the girls. The

cut of the clothing and decorations highlights the distinctive Iroquois

dress. One of the best and earliest descriptions of the Fish Dance appears

in Lewis Henry Morgan's 1851 study of the Iroquois, League of the Haudenosaunee:

-

- The two singers seating themselves in the centre of

the room facing each other, and using the drum and rattle to mark time,

and increase the volumes of the music. The step was merely an elevation

from heel to toe, twice repeated upon each foot alternately The dance was

commenced by the leader, who took the floor, followed by others, and walked

to the beat of the drum. When the song commenced, each alternate dancer

faced round, thus bringing the column into sets of two each, face to face,

those who turned dancing backwards, but the whole band moving around the

roomEach song or tune lasted about three minutes. At the end of the first

minute there was a break in the music, and the sets turned, thus reversing

their positions; at the end of the second there was another change in the

music, in the midst of which the sets turned again which brought them back

to their original positions.

-

-

- GWEE SAS SE or War Dance

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Gouache on composition board, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1942.93.14

-

- Iroquois war dances are identified by the couched arched

neck posture that the dancers assume to the accompaniment of a deep-toned

regular beat of a water drum. The head piece is made of deer hair; the

position of the eagle feather denotes victory. The dancers carry the traditional

Iroquois ball-headed club; the background design is the thunderbird.

-

- In earlier times performed as a celebration of military

exploits, this dance was transformed by Ganeodiyo (Handsome Lake) into

a dance of thanksgiving and encouragement to "Our Grandfathers, the

Thunderers, who carry with them water to renew life." The dance is

done in April during the Thunder Ceremony, and on the "Life Supporters

Day" during Midwinter. The War Dance is always followed by the Peace

Dance.

-

- The Thunder Dance, is designed to please the spirit

of thunder, He-no, when the first thunder of the year is heard. The dancers

assemble outside the council house, a faithkeeper makes an opening address

and the dance begins. The line of dancers move into the longhouse. He-no

delights in war songs and these are to please him. Tobacco is burned and

a Thanksgiving speech is made to thank He-no for this help in the past

and the future. (From the Code of Handsome Lake.)

-

-

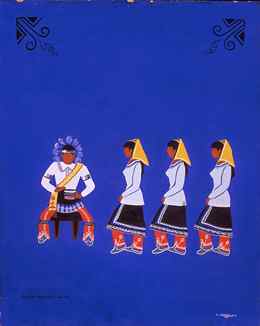

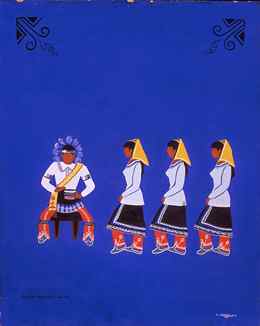

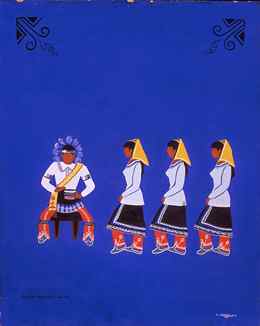

- A.GOO.GWA.KA.O-WA.NA or Women'

s Dance

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Gouache on composition board, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1942.93.17

-

- This dance is a reenactment of the Creation story:

-

- When Skywoman fell from the world onto the turtle's

back, one of the animals brought her some earth from the land below. She

placed this on the turtle, then walked around his back in a circle, following

the sun. Because the space was small, her steps were like a shuffle, which

is why one women's dance is called the "Shuffle Dance." She formed

the land in this way, creating Mother Earth.

-

- The Haudenosaunee have always honored women, who have

strong social and political roles in society. Descent and property pass

from mother to daughter; men and women belong to the clan (extended family

lineage) of their mother. Although men become chiefs, it is women who appoint

them - and carry the power to remove them from office if necessary.

-

-

Serigraphy or Silkscreen

Printmaking can be divided into four main categories consisting

of relief, intaglio, planography, and serigraphy. The oldest form of printmaking

dates from the eleventh century and is called relief; woodcuts are the most

common. Developed in the fifteen century, intaglio---derived from an Italian

word for incise or cut into--- includes all forms of engraving and etching.

Planography, first developed in the late eighteenth century is the easiest

and least expensive form of printmaking and includes lithography. Although

serigraphy or silk screening traces its concept back to fifteenth century

stencil-colored prints, the technique was developed for commercial purposes

in the 1920s. By the late 1930s artists began using the silkscreen print

process because of its technical simplicity.

The two serigraphic prints shown here are early examples

of this process. According to his family, Tom Two Arrows was particularly

adept with this process. To make a silk- screened print, a design is drawn

onto a screen of silk or nylon. The areas not to be printed are masked by

liquid glue or stencils. Ink is then forced through the screen with a squeegee.

The image, printed on paper or any other flat surface such as cloth, mylar,

or metal, is created by the holes in the screen through which the ink is

allowed to pass. Serigraphs generally involve two or more colors, requiring

a separate screen for each color.

-

- RUNNING DEER

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Color silkscreen on paper, 1942

- AIHA Purchase, 1943.103.2

-

- The deer represents the source of many essentials of

life to native people. In addition to food, the deer provides bone for

tools and gaming pieces, sinew for thread, skins for clothing, horn for

tools, hooves for dance rattles. The Haudensaunee admiration for

the qualities of the deer is shown by its adoption as one of the nine clan

animals. The symbol for a chief's authority is a set of deer antlers placed

upon his gustoweh or headdress.

-

- We give thanks and greetings to all animals of which

we know the names. They are still living in the forest and other hidden

places and we see them sometimes. Also from time to time they are still

able to provide us with food, clothing, shelter and beauty, This gives

us happiness and peace of mind because we know that they are still carrying

out their instructions as given by the Creator. (From

Thanksgiving Address.)

-

-

- TWO WOMEN POUNDING CORN

- Thomas J. Dorsey or Tom Two Arrows (1920-1993)

- Color silkscreen on paper, c. 1943

- Gift of Tom and Donna Nelson, 1993.40

-

-

(above: Thomas J. Dorsey, Jr. (Tom Two Arrows) (1920-1993),

A Goo Gwa Ka O-Wa Na or Women's Dance, 1942, gouache on composition

board, ht. 20 1/16 in., w. 16 inches, inscribed, lower left: "A

GOO GWA KA O-WA NA"; signed, lower right: "DORSEY".

Albany Institute of History & Art Purchase, 1942.93.17)

(above: Thomas J. Dorsey, Jr. (Tom Two Arrows) (1920-1993),

Da Hoon Gu Gwa A Gwa or Lacrosse, 1942, gouache on composition

board, ht. 20 1/8 in., w. 16 inches, inscribed, upper left: "DA

HOON GU GWA A GWA"; signed, lower right: "DORSEY",

Albany Institute of History & Art Purchase, 1942.93.7)

Editor's note: Resource Library readers may also

enjoy:

On June 16, 2009 the Rockwell Museum of Western Art sent

to TFAO a news release concerning an exhibition featuring Iroquois glass

beadwork being shown there May 23 through October 4, 2009. While the news

release did not contain enough text for an article, it is presented below

to provide an insight into another facet of Iroquois art.

- The Rockwell Museum of Western Art in Corning, NY will

feature the special exhibition, Sewing the Seeds: 200 Years of Iroquois

Glass Beadwork, beginning May 23 and will be on display through

October 4. The summer glass exhibition will feature over 300 of

the finest pieces of Iroquois beadwork ever created by Haudenosaunee bead

workers.

-

- The exhibition will exhibit imaginative images of flora

and fauna on pieces of beadwork adorned with variety of a purses, moccasins,

frames vast array of colors will feature beadwork in the shape of strawberries,

beaded animals, as well as Indian-made dolls with beaded clothing. The

flowers, plants, animals, and birds adorn pincushions, picture frames,

and many other of the eighty types of Iroquois beadwork. A highlight of

the exhibit will be a 21st century recreation of a traditional woman's

outfit such as those worn by Haudenosaunee women in ceremonies, pow wows,

and festivals for over three hundred years

-

- The beadwork comes from the 2000-piece collection of

Iroquois beadwork assembled by Dolores Elliott of Binghamton, NY. Elliott's

collection is one of the largest collections in the world. She has authored

several books concerning the history and identification of Iroquois beadwork

including Flights of Fancy and Iroquois Beadwork Vol 1: A Short History.

Her articles have appeared in BEADS: The Journal of the Society of Bead

Researchers and in three journals of the Bead Society of Great Britain

along with dozens of newspapers and historical society newsletters. She

has presented dozens of presentations on Iroquois beadwork at colleges,

museums, and meetings of social groups, historical societies, and archaeology

clubs.

-

- Pieces from the collection have been shown at the New

York State Museum in Albany, the Mashantucket Pequot Museum in Connecticut,

the United Nations Headquarters in New York City, the Bruce Museum in Connecticut,

the Woolaroc Museum in Oklahoma, the Seneca Iroquois Museum in Salamanca,

the Woodland Cultural Centre in Brantford, Ontario, and closer to home

in Binghamton, Ithaca, Elmira, Vestal, Oneonta, and Syracuse.

rev. 6/16/09

Read more articles and essays concerning this institutional

source by visiting the sub-index page for the Albany

Institute of History and Art in Resource

Library.

Search Resource

Library for thousands of articles and essays on American art.

Copyright 2009 Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc., an Arizona nonprofit corporation. All rights

reserved.