Editor's note: The Phoenix Art Museum provided

source material to Resource Library for the following article or

essay. If you have questions or comments regarding the source material,

please contact the Phoenix Art Museum directly through either this phone

number or web address:

A Century of Retablos:

The Janis and Dennis Lyon Collection of New Mexican Santos, 1780-1880

October 6, 2007 - February 3, 2008

A rich

tradition of religious painting flourished in New Mexico during the years

prior to statehood in 1912. In this Spanish colonial era, several painters

and their workshops created painted wood panels depicting various Christian

saints and holy figures, earning for themselves the title of santeros

-- saint makers. These colorful, narrative panels, or retablos, were

worshiped in churches and private homes. Their heyday in the 18th and 19th

centuries remains a largely overlooked episode of the history of art in

New Mexico. The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue introduce retablos

to our museum audience and inform the public of the methods of creating

these beautiful panel paintings.

A Century of Retablos features

94 wooden panels, all created during the colonial period, from one of the

finest private collections of retablos in the world. The Janis and

Dennis Lyon collection encompasses the breadth and depth of the retablo

tradition. This exhibition provides the first opportunity for the Lyon collection

of retablos to be available for the public's viewing.

Introduced by the Spanish as a means of converting the

Indian population, retablos became popular throughout the Southwest.

In and around the industrialized Mexico City, retablos were most frequently

painted on tin by artists with knowledge of academic artistic training.

In remote, northern New Mexico, however, the self-taught artists used materials

largely derived from nature, mixing their own pigments to decorate the roughly-cut

wooden panels. While the images recall folk-art traditions, an iconography

provided by the Catholic church was strictly followed. It was important

that the stories of the saints could be understood by the largely illiterate

population.

The opening of the Santa Fe Trail in 1821 marked the beginning

of the end of the New Mexican retablos tradition. Traders not only

brought tin into the region, but also inexpensive, framed prints of holy

figures, which eventually forced the santeros out of business.

This exhibition is groundbreaking in its approach, recognized

as such by the National Endowment for the Arts with a grant for support

from their American Masterpieces: Three Centuries of Artistic Genius

program. Previously unconsidered questions and the biographies of various

santeros are explored, as well as the relationships among artists,

workshops, and patrons. The expert research by Charles Carrillo and Father

Thomas Steele is the basis of this effort. Carrillo is an accomplished anthropologist

who is well-respected in his field and has been widely published over the

past twenty years. He is also a leading contemporary santero. Father

Thomas Steele is a highly-regarded author and social historian who studies

Hispanic life in early New Mexico. Together, their research sheds new light

on the social history and artistic significance of colonial retablos,

examining not only the physical and aesthetic nature of the decorative panels,

but also the ways these objects were used in churches and as private devotional

objects.

Written by Carrillo and Steele, the 240 page, full-color,

exhibition catalgoue is published by Hudson Hills Press, one of the country's

most respected American art publishers. The volume contains a complete color

catalogue of the collection with descriptive essays for each retablo,

examining the iconography and social history. It includes critical essays,

a chronology, catalogue entries, and 92 color plates. The essays explore

themes of art and religious value, artists' interpretations of religious

symbolism, and the stylistic development of the santeros.The book

will be of interest general audiences and scholars interested in New Mexican

Hispanic art, the Spanish colonial period, and the retablo tradition

in general.

Organized by Phoenix Art Museum, the exhibition and accompanying

catalog have been generously supported by the National Endowment for the

Arts through its American Masterpieces: Three Centuries of Artistic Genius

program. Major support for the exhibition has been provided by American

Express Company.

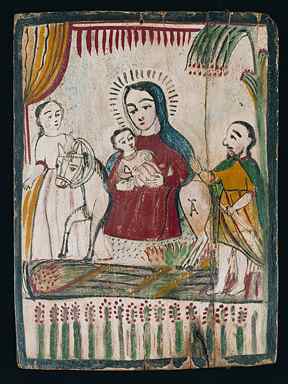

(above: Jose Rafaél Aragón, Saint John

the Baptist, natural pigments on wood panel. The Janis and Dennis Lyon

Collection)

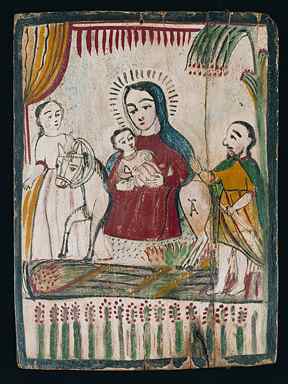

(above: Jose Rafaél Aragón, The Flight

into Egypt, natural pigments on wood panel. The Janis and Dennis Lyon

Collection)

(above: Jose Rafaél Aragón, Saint Felix,

natural pigments on wood panel. The Janis and Dennis Lyon Collection)

(above: The Eighteenth-Century Novice, Saint Gertrude,

oil paint on wood panel. The Janis and Dennis Lyon Collection)

(above: Pedro Antonio Fresquís, Our Lady of Guadalupe,

natural pigments on wood panel. The Janis and Dennis Lyon Collection)

Wall texts from the exhibition

- Introductory panel

-

- Introduced to the Southwest by the Spanish, retablos flourished

as a devotional art form for roughly a century in colonial New Mexico.

Although the artists who made them, called santeros (saint-makers),

were largely self taught, they followed a code of symbols set forth by

the Catholic Church in their depictions of various holy figures. This use

of established symbols, or iconography, allowed for a largely illiterate

populace to identify each image, which proved instrumental to the conversion

of Indians to Christianity. These painted, wooden panels were venerated

in churches and private homes alike.

-

- Janis and Dennis Lyon have been serious connoisseurs and collectors

of New Mexican retablos for more than 30 years and have created

one of the world's finest private collections. Interested in coming as

close to the hands of these early painters as possible, they diligently

choose only those works with little or no restoration. Organized by Phoenix

Art Museum, this exhibition is made possible through the dedication and

generosity of Janis and Dennis Lyon, and the expertise of Dr. Charles Carrillo

and Father Thomas Steele.

-

-

- Second panel

-

- The santeros of New Mexico worked primarily with local, natural

supplies. Starting with a wooden panel, usually ponderosa pine, artists

applied a gesso made from baked gypsum and animal-hide glue or wheat flour

paste as a binding agent to hold the paint. Since few imported dyes were

available, artists made the majority of their water-based pigments made

from local clays, minerals, carbon soot, plants, barks, roots, and flowers,

which they then applied using homemade brushes. They used a piñon-sap

varnish for waterproofing.

-

- Burn marks are visible on several of the panels' bases. Specialists

and collectors long believed that such marks were caused by burning candles

left too close to the wooden objects. Recently research, however, indicates

that such markings were intentional. It is now believed that carbon removed

from the burned areas was used for medicinal purposes (for example, to

rub on an afflicted body part or stir into food or water), or possibly

preventative purposes (to toss into the air or a stream against natural

dangers, like fire, severe wind, or flood).

-

- New Mexican santeros worked on wooden panels, unlike their counterparts

in Mexico, who painted on tin. Tin, however, became more readily available

in New Mexico with the opening of the Santa Fe Trail in 1821, marking the

beginning of the end of the New Mexican retablos tradition. Traders

not only brought tin into the region, but also inexpensive, framed prints

of holy figures, which eventually forcing the santeros out of business.

-

- The Santeros (Saint-Makers)

-

- The Eighteenth-Century Novice (active c. 1780)

- An emigrant from southern New Spain (modern-day Mexico), this artist

was familiar with Spanish Baroque painting. He worked in oil paint, which

was rare for a New Mexican santero.

-

- Pedro Antonio Fresquís (1749 - after 1831)

- He was likely the earliest santero born in New Mexico and is believed

to have had apprentices or assistants who worked in a taller, or workshop.

-

- The Laguna Santero (active c. 1790 - 1815)

- Unknown by name, this santero is identified from a large altar screen

at the mission church at the Pueblo of Laguna. He is credited with making

more large-scale Colonial art than any other santero. His workshop also

produced devotional sculptures, called bultos.

-

- Molleno (active c. 1800 - 1830)

- A follower or apprentice of the Laguna Santero, healso created several

altar screens. The artist's name is not found in archival records and is

possibly a nickname preserved in the collective memory of the residents

of the Cañon Chimayó, north of Santa Fe.

-

- The A.J. Santero (active c. 1830 - 1850)

- An anonymous, educated santero identified by the initials "A.J."

found in the corner of a single retablo. He was not prolific, and there

are less than 50 retablos known by him.

-

- The Quill Pen Santero (active c. 1820 - 1850)

- This santero drew fine facial features with a quill pen, and was influenced

by Molleno. His use of what appear to be Pueblo Indian designs has led

some scholars to suggest that he was of American Indian heritage. His production

was limited, and his retablos are among the rarest in New Mexico.

-

- José Aragón (born c. 1781-89 - d. post - 1850)

- A prolific artist who made hundreds of retablos and bultos, Aragón

signed many of his works, unlike most santeros of his era. He was born

in Santa Fe and was an older brother to fellow santero, José Rafael

Aragón.

-

- The Christmas Santero (c. 1830s or 1840s)

- A short-lived sub-group of the Workshop of José Aragón,

recognized by the predominant use of bright red and green paints.

-

- The Arroyo Hondo Painter (active 1820s - 1840s)

- Named after an altar screen from the Church of Nuestra Señora

de Dolores de Arroyo Hondo, about 12 miles outside of Taos, this artist's

work is closely related to that of José Aragón. He was earlier

identified as the "Dot-Dash Painter" because of his use of decorative

elements. There is an extensive body of work attributed to this painter,

who also created bultos.

-

- José Rafael Aragón (born c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- He was arguably the finest and most talented santero of his era. A

highly prolific painter and sculptor, he created most of the altar screens

for the communities along the high road to Taos. Born and raised in Santa

Fe, he belonged to a network of artisan families of carpenters and woodworkers.

He resettled in Quemado in 1835.

-

- The Workshop (Taller) of José Rafael Aragón (c. 1830s-

c.1870s)

- José Rafael's son, Miguel, is believed to have followed in his

father's footsteps and worked at his father's workshop. Studies suggest

that followers continued to paint in the style of José Rafael after

his death.

-

- José Manuel Benavides (c. 1798 - post 1852)

- Previously identified as the anonymous Santo Niño Santero, Benavides

was a sculptor and painter who likely shared a workshop with José

Rafael Aragón.

Wall labels from the exhibition

Our Lady of Guadalupe

-

- Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe),

is Mexico's and the Southwest's most beloved religious image and, not surprisingly,

is featured more often than any other holy figure in the Lyon Collection.

-

- From December 9 to 12, 1531, the Virgin Mary is believed to have appeared

four times to Juan Diego on the hill of Tepeyac, near Mexico City. She

requested that an abbey church be built on the site. When he asked for

a sign, she told him to gather roses in his tilma, or cloak. Later,

when he opened the tilma for the skeptical Spanish bishop, Fray

Juan de Zumárraga, the image of the Virgin was miraculously imprinted

on the cloth.

-

- Juan Diego was canonized in 2002, and his feast day is celebrated on

December 9. The feast for the Virgin of Guadalupe is December 12.

-

- 1) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe)

- At the bottom is a baptismal font, likely in reference to the thousands

of Indians who sought baptism after hearing of Mary's appearance to San

Juan Diego.

-

- 2) Pedro Antonio Fresquís (1749 - after 1831)

- Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe)

-

- 3) Molleno (active c. 1800 - 1830)

- Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe)

-

- 4) Pedro Antonio Fresquís (1749 - after 1831)

- Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe)

-

- 5) Workshop of José Aragón (c. 1820s - 1840s)

- Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe)

- New Mexican santeros made this type of retablo to relate to the Virgin's

four apparitions to San Juan Diego. In the lower right corner, he reveals

the miraculous image. The awkward shape of the mandorla, or halo surrounding

the Virgin, may represent San Juan Diego's tilma, or cloak.

-

- 6) The Laguna Santero (active c. 1790 - 1815)

- Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe)

-

- 7) The Arroyo Hondo Painter (active 1820s - 1840s)

- Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe)

-

-

- Holy Family and Christ

-

- 1) The Workshop (Taller) of José Rafael Aragón (c. 1830s

- 1860)

- El Santo Niño de Atocha (The Holy Child of Atocha)

-

- 2) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- La Huida al Egipto (The Flight into Egypt)

- Led by a wingless angel, the family of Christ flees persecution from

King Herod's soldiers.

-

- 3) José Aragón (c. 1781-89 - after 1850)

- Jesús con la Cruz a Cuestas (Jesus Bears the Cross on His

Back)

-

- 4) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- La Huida al Egipto (The Flight into Egypt)

-

- 5) The Arroyo Hondo Painter (active 1820s - 1840s)

- Jesús con la Cruz a Cuestas (Jesus Bears the Cross on His

Back)

- Christ is shown with multiple wounds of the Passion (Latin passio,

"suffering"), including a bloody mark on his left cheek, known

in New Mexico as El Beso de Judas, (The Kiss of Judas).

-

- 6) The Christmas Santero (active c. 1830s or 1840s)

- Cristo Crucificado y Calvario (Christ Crucified and Calvary)

-

- 7) Pedro Antonio Fresquís (1749 - after 1831)

- Cristo Crucificado (Christ Crucified)

-

- 8) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- M 3) Las Cinco Llagas (The Five Wounds)

- This image symbolizes the five wounds Christ suffered on the cross:

two for the hands, two for the feet, and the spear to the side. The three

wedges inside the heart likely represent the nails used in the Crucifixion.

-

- 9) The Christmas Santero (active c. 1830s or 1840s)

- La Santa Cruz con San Juan Evangelista y Nuestra Señora de

Delores (The Holy Cross with Saint John the Evangelist and Our Lady of

Sorrows);

- or, La Cruz Vestida con José de Arimatea (or Nicodemos)

y María Magdalena (The Vested Cross with Joseph of Arimathea [or

Nicodemus] and Mary Magdalen);

- or, La Santísima Cruz y El Santo Lino con Figuras Dolientes

(The Most Holy Cross and the Holy Cloth with Mourning Figures)

-

- 10) Pedro Antonio Fresquís (1749 - after 1831)

- Cristo Crucificado (Christ Crucified)

- The skull at the base of the cross symbolizes Adam, the first man,

believed to be the original sinner. The blood from the crucified Christ

is intended to cleanse mankind of its sins. People prayed to images of

Christ so that he may offer supernatural gifts: salvation of the world,

peace, pardon of sin, bearing of sufferings, piety, or a peaceful death.

- Joseph and Mary

-

- 1) The Laguna Santero (active c. 1790 - 1815)

- San José (Saint Joseph)

-

- 2) Pedro Antonio Fresquís (1749 - after 1831)

- San José (Saint Joseph)

- Joseph holds hollyhocks, called "the rod of Saint Joseph"

in New Mexico.

-

- 3) The Quill Pen Santero (active c. 1820 - 1850)

- San José (Saint Joseph)

-

- 4) José Aragón (c. 1781-89 - after 1850)

- San José (Saint Joseph)

-

- 5) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- Nuestra Señora Esposa de José (Our Lady Spouse of

Joseph)

- This unique depiction of Mary is likely one of a pair of images, the

other depicting Joseph.

-

- 6) José Manuel Benavides (c. 1798 - after 1852)

- Señor San José Esposo de María (Lord Saint

Joseph Spouse of Mary)

- Joseph is the patron of the universal Church, fathers, families, orphans,

travelers, carpenters and workers. To aid in selling a house, people frequently

bury statues of Saint Joseph in the yard. Benavides likely copied this

image from an engraving of a sculptural bust of Joseph on a pedestal.

-

- 7) The Quill Pen Santero (active c. 1820 - 1850)

- San José (Saint Joseph)

-

- 8) The A.J. Santero (active c. 1830 - 1850)

- San José (Saint Joseph)

-

-

- Mary and the Holy Trinity

-

- 1) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- El Alma de María (The Soul of Mary); or, La Santísima

Trinidad con María (The Most Holy

- Trinity with Mary)

- Originally identified as representing the soul of Mary, specialists

now believed that this retablo represents the Most Holy Trinity with Mary:

the baton represents God the Father's scepter of omnipotence, and the dove

represents the Holy Spirit that visually connects the Christ Child with

the symbol of God.

-

- 2) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- La Virgen de los Reyes Católicos y La Santísima Trinidad

(The Virgin of the Catholic Kings and the Most Holy Trinity)

- This retablo may be understood as a form of political propaganda. On

Mary's right is King Ferdinand VII of Spain, and to her left is the Archbishop

Saint Leander of Seville, or possibly his younger brother Saint Isidro.

Aragón showed the king in a favorable light by associating him with

holy figures.

-

-

- Variations of Our Lady

-

- 1) Workshop of the Laguna Santero (c. 1800 - 1815)

- Nuestra Señora de San Juan de los Lagos (Our Lady of Saint

John of the Lakes)

- Standing on a pedestal and flanked by a pair of candles, this image

was based on a shrine at San Juan de los Lagos in Mexico.

-

- 2) Pedro Antonio Fresquís (1749 - after 1831)

- Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows)

-

- 3) The Workshop (Taller) of José Rafael Aragón (c. 1830s

- 1860)

- Nuestra Señora de la Cueva Santa (Our Lady of the Sacred

Cave)

-

- 4) Workshop of José Aragón (c. 1820s - 1840s)

- Nuestra Señora de Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows)

- The dagger in Mary's heart powerfully symbolizes severe grief. Mary's

sorrow over Jesus' death makes her patron of strength in suffering, compassion

for others, and help in childbirth and with children.

-

- 5) The Arroyo Hondo Painter (active 1820s - 1840s)

- Nuestra Señora del Carmen (Our Lady of Mount Carmel)

- Worshippers believe Our Lady of Mount Carmel is an intercessor for

souls in Purgatory, which appear at the bottom of the panel. The crack

on the left side was repaired using native techniques.

-

- 6) Pedro Antonio Fresquís (1749 - after 1831)

- Nuestra Señora de la Manga (Our Lady of the Sleeve)

- Only two known examples of this subject exist from New Mexico, both

by Fresquís. The use of crosshatching lines suggests the artist

copied the image from an engraving.

-

- 7) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- Nuestra Señora de Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows)

- The three small holes at the bottom edge of the Virgin's gown indicate

that an object or objects were once attached to the bottom of the retablo.

-

- 8) Workshop of José Aragón (c. 1820s - 1840s)

- Nuestra Señora Refugio de Pecadores (Our Lady, Refuge of

Sinners)

-

- 9) José Aragón (c. 1781-89 - after 1850)

- Nuestra Señora de Carmen (Our Lady of Mount Carmel)

-

- 10) Molleno (active c. 1800 - 1830)

- Nuestra Señora de San Juan de los Lagos (Our Lady of Saint

John of the Lakes)

-

- 11) Workshop (Taller) of Fresquís (c. 1800 - 1830s)

- Nuestra Señora de Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows)

-

- 12) The Arroyo Hondo Painter (active 1820s - 1840s)

- Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción (Our

Lady of Immaculate Conception)

-

- 13) The Arroyo Hondo Painter (active 1820s - 1840s)

- Nuestra Señora de Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows)

-

- 14) Workshop (Taller) of Fresquís (c. 1800 - 1830s)

- Nuestra Señora del Rosario (Our Lady of the Rosary)

-

- 15) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- Nuestra Señora de Merced (Our Lady of Mercy)

-

- 16) Pedro Antonio Fresquís (1749 - after 1831)

- Nuestra Señora del Rosario (Our Lady of the Rosary)

-

- 17) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- Nuestra Señora del Carmen (Our Lady of Mount Carmel)

-

- 18) Pedro Antonio Fresquís (1749 - after 1831)

- Nuestra Señora del Carmen (Our Lady of Mount Carmel)

- Both the Virgin and the Christ Child hold a small, red, rectangular

scapular, pieces of woolen cloth worn as a symbol of devotion.

- Saints

-

- The saints in the next three sections on this wall are arranged in

roughly chronological order of their life dates, ranging from the 1st to

the 16th century.

-

- 1) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- San Juan Bautista (Saint John the Baptist)

- Outside of altar screens for churches, this is one of the largest known

retablos by Aragón. Saint John is shown in a slightly turned, contrapposto

pose, which is common in Baroque sculpture. However, the artist lacked

knowledge in rendering perspective and John's legs appear as if crossed.

-

- 2) The Arroyo Hondo Painter (active 1820s - 1840s)

- San Acacio (Saint Acacius of Mount Ararat)

- Although Saint Acacius was a 3rd century Roman centurion, the artist

dressed him as a Spanish soldier of the early 19th century.

-

- 3) The Workshop (Taller) of José Rafael Aragón (c. 1830s

- 1860)

- San Acacio (Saint Acacius of Mount Ararat)

-

- 4) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- San Acacio (Saint Acacius of Mount Ararat)

-

- 5) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 -1862)

- San Nicolás de Myra/Bari (Saint Nicholas of Myra/Bari)

- A patron to sailors, referenced by the clouds above his head, Saint

Nicholas was also known to be generous. He once gave an anonymous gift

of gold for the dowries of three sisters, thus saving them from prostitution.

He died in 342, and in 1087 his bones were robbed from Myra, in modern-day

Turkey, and taken to Bari, Italy. They were eventually carried throughout

Europe, where he became a popular saint. The Dutch changed his name to

Sint Klaes, while the English called him Santa Claus.

-

- 6) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- San Félix (Saint Felix)

-

- 7) Workshop (Taller) of Fresquís (c. 1800 - 1830s)

- San Gerónimo (Saint Jerome)

-

- 8) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- San Casiano de Imola (Saint Cassian of Imola)

-

- 9) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- San Isidro Labrador (Saint Isidore the Worker)

- Saint Isidore is the patron saint of ranchers, farmers, and good harvests.

He protects against locusts, earthquakes, bad weather and bad neighbors.

New Mexican people believed that Isidore, a Spaniard, lived with his wife,

Santa Maria, near the Rio Grande.

-

- 10) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- San Isidro Labrador (Saint Isidore the Worker)

-

- 11) Pedro Antonio Fresquís (1749 - after 1831)

- San Norberto (Saint Norbert)

-

- 12) The Arroyo Hondo Painter (active 1820s - 1840s)

- San Isidro Labrador (Saint Isidore the Worker)

- Saint Isidore stands to the side of two oxen that pull a single-handled

plow, an ancient implement used by New Mexicans as late as the turn of

the 20th century.

-

Saints

-

- 1) Workshop of José Aragón (c. 1820s - 1840s)

- Santa Rosalía de Palermo (Santa Rosalia of Palermo)

-

- 2) The A.J. Santero (active c. 1830 - 1850)

- Santa Rosalía de Palermo (Saint Rosalie of Palermo)

-

- 3) The A.J. Santero (active c. 1830 - 1850)

- San Francisco de Asís (Saint Francis of Assisi)

- Saint Francis of Assisi created three religious orders: the first for

priests and brothers, the second for nuns and the third for married or

single men and women. Aimed at converting the native population, the Franciscan

Order in New Mexico dates back to 1540 and the expeditions of Coronado.

They maintained several Franciscan missions around the Santa Fe region

in the 19th century.

-

- 4) Pedro Antonio Fresquís (1749 - after 1831)

- San Antonio de Padua (Saint Anthony of Padua)

-

- 5) The Quill Pen Santero (active c. 1820 - 1850)

- San Antonio de Padua (Saint Anthony of Padua)

- Born in Lisbon, Portugal, in 1195, Saint Anthony was a university-educated

Augustinian, ordained around 1220. Saint Francis gave Anthony a mandate

to teach, and his mission sent him throughout Italy and into France and

Spain. He died in 1231 in the outskirts of Padua.

-

- 6) José Aragón (c. 1781-89 - after 1850)

- San Antonio de Padua (Saint Anthony of Padua)

-

- 7) Workshop (Taller) of Fresquís (c. 1800 - 1830s)

- San Antonio de Padua (Saint Anthony of Padua)

-

- 8) José Rafael Aragón (c. 1783-96 - 1862)

- San Antonio de Padua (Saint Anthony of Padua)

- This retablo stands out as one of the most accomplished works by Aragón.

Saint Anthony kneels as he exchanges hearts with the Christ Child, powerful

depicting their spiritual union. A basket of hearts on the base of the

altar table symbolizes the souls of believers.

-

- 9) Pedro Antonio Fresquís (1749 - after 1831)

- San Antonio de Padua (Saint Anthony of Padua)

-

- 10) The Laguna Santero (active c. 1790 - 1815)