Editor's note: The Frist Center for the Visual

Arts provided source material to Resource Library Magazine for

the following article or essay. If you have questions or comments regarding

the source material, please contact the Frist Center for the Visual Arts

directly through either this phone number or web address:

Coming Home: American Paintings,

19301950, from the Schoen Collection

June 4 - September 6, 2004

The paintings in Coming

Home: American Paintings, 19301950, from the Schoen Collection depict

the  sweeping social, artistic,

and political transformations that took place during two of the most critical

decades in American history. Featuring approximately 60 paintings, Coming

Home includes works by such acclaimed painters as Regionalists Thomas

Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry; Magic Realist Paul Cadmus; Surrealist

Federico Castellon; and Social Realists Ben Shahn and Raphael Soyer. The

time period of the exhibition extends from the Wall Street Crash of 1929

and proceeds through the years of the Great Depression, concluding with

images showing the impact of World War II on the home front. (right:

Thomas Hart Benton, Fisherman at Sunset, 1947, gouache on

paper, 15 x 21 inches)

sweeping social, artistic,

and political transformations that took place during two of the most critical

decades in American history. Featuring approximately 60 paintings, Coming

Home includes works by such acclaimed painters as Regionalists Thomas

Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry; Magic Realist Paul Cadmus; Surrealist

Federico Castellon; and Social Realists Ben Shahn and Raphael Soyer. The

time period of the exhibition extends from the Wall Street Crash of 1929

and proceeds through the years of the Great Depression, concluding with

images showing the impact of World War II on the home front. (right:

Thomas Hart Benton, Fisherman at Sunset, 1947, gouache on

paper, 15 x 21 inches)

During the 1930s and 1940s, many artists turned to subject

matter that reflected their experiences of the locales in which they lived

and worked. Known as Regionalism or American Scene painting, this trend

emerged in all corners of the country, as artists told visual stories about

the people in towns, cities, and the countryside who enacted their quotidian

lives with heroism, humor, or tenacity in the face of economic hardships.

These artists were often supported by such programs as

the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and its division, the Federal Arts

Project (FAP); the Farm Security Administration (FSA); and the Treasury

Department's Section of Fine Arts (SFA). Throughout the 1930s, these New

Deal agencies encouraged artists to document the American experience. Many

who took part in Federal art programs sought to capture the distinctive

characteristics of the country's regions and its people, in ways that could

be understood by everyone who saw them. Even artists who received no government

support often embraced the idea of an art that would speak directly of people's

own lives.

The first two galleries in the exhibition are arranged

to represent a visual trip across America. It begins with scenes  of New York by Isaac Soyer, Joseph Hirsch, and Eugenie

MacEvoy, and then continues with depictions of steamy Southern nights by

Charles Shannon and William Hollingsworth; Midwestern farms and farmers

by Guy MacCoy and John Steuart Curry; and people living and working in the

inhospitable environments of Western deserts and mountains, as shown in

paintings by Peter Hurd and Alfredo Ramos Martinez. (right: Louis

Freund, Transcontinental Bus, 1936, oil on panel, 25 x 31 inches)

of New York by Isaac Soyer, Joseph Hirsch, and Eugenie

MacEvoy, and then continues with depictions of steamy Southern nights by

Charles Shannon and William Hollingsworth; Midwestern farms and farmers

by Guy MacCoy and John Steuart Curry; and people living and working in the

inhospitable environments of Western deserts and mountains, as shown in

paintings by Peter Hurd and Alfredo Ramos Martinez. (right: Louis

Freund, Transcontinental Bus, 1936, oil on panel, 25 x 31 inches)

While the Regionalists sought a distinctively American

style and subject matter, artists in the third gallery reflected developments

in art beyond the nation's borders. For them, it was less important to convey

their experience of their immediate environments than to create beauty or

convey a sense of fantasy or mystery. Jessie Arms Botke's exquisite Flamingoes

and Lotus (ca. 1939) recalls the influence of Japanese art popular in

late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century decorative arts. Painted

with equal clarity and grace, the Magic Realist artist Paul Cadmus's Shells

and Figure (1940) combines a love for the fantastic with a stylistic

precision that makes the work seem to have been painted from direct observation.

Helen Lundeberg's Poetic Justice (1945) similarly combines

the meticulous technique of Northern Renaissance artists with the dream

imagery of European Surrealism. Although not prominently featured in the

Schoen collection, many of the artists in this section helped pave the way

for the generation of Abstract Expressionists that came in the 1940s, who

were inspired by the Surrealist goal of giving aesthetic form to the unconscious

realm.

The last section of Coming Home is dedicated to

works that document the Great Depression and the homefront during World

War II. In 1931, a severe and long-lasting drought hit Midwestern and Western

states, further intensifying the devastation of the nation's economy incurred

by the Wall Street crash of 1929. Millions of Americans suffered unemployment,

poverty and the loss of their homes during these years. In the Dust Bowl,

crops were destroyed as blinding dust storms swept across the panhandles

of Texas and Oklahoma, western Kansas, and the eastern portions of Colorado

and New Mexico. Many people abandoned their farms and traveled the country

in search of agricultural work, as dramatized in the classic novel The

Grapes of Wrath. Like author John Steinbeck, artists William Gropper

in The Last Cow (1937), Mervin Jules in Bare Statement (1941),

and John Langley Howard in Hooverville (1933) focused attention on

the plight of these displaced people through powerful narrative scenes,

many of which they had observed firsthand as they traveled through the region.

Other artists, angered by the government's slowness in

alleviating the suffering of the homeless and jobless, and by the often

brutal tactics of local authorities in their treatment of dispossessed people,

were moved to a more activist stance with their paintings. Often members

of the political left, Social Realists like Ben Shahn in Unemployed (1938),

Henry Billings in The Arrest No. 2 (1936), and William Gropper in

The Incumbent (ca. 1938) used their art to expose these injustices,

which they believed were contrary to the egalitarian spirit of democracy.

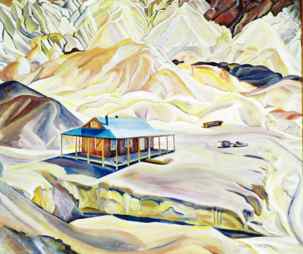

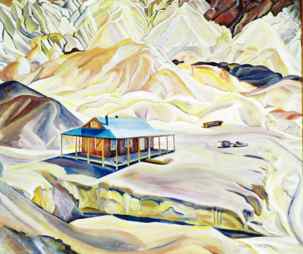

When the nation entered World War II, millions of its citizens

found jobs in the defense industry, reducing unemployment and helping to

revive the economy. Artists were among the sixteen million Americans who

joined the armed forces, often serving as war reporters and correspondents.

Those who stayed behind frequently portrayed their countrymen supporting

the war effort through factory and farm work. Clarence Holbrook Carter's

Good Crop and Isaac Soyer's Defense Plant Worker (both 1942)

conclude the exhibition with symbols of strength and hope that portend a

new beginning for the nation. (right: Helen Forbes, Mountains

and Miner's Shack, 1940, oil on canvas, 34 x 40 inchcs)

As the economy improved, federal relief and patronage were

phased out, and artists who had participated in New Deal art programs returned

to the private sector or began teaching in colleges and universities across

the country. Many of their students were veterans benefiting from a new

government program, the G.I. Bill of 1944, which made higher education available

to the men and women who had served in the military.

ABOUT THE COLLECTOR

Jason Schoen has vigorously pursued his passion for collecting

American art of the 1930s and 1940s for more than 20 years. While he has

acquired important examples of Social Realism, abstraction, and Surrealism,

Schoen has been most interested in having his collection foster an understanding

of the regionalist impulse that appeared in much of the period's art. "A

goal of mine," he writes," has been to create a collection of

regional art, which can serve as a study collection and an introduction

to an era, as a slice of life and a window onto an important period in American

history."

Editor's note: RLM readers may also enjoy:

Please Note: TFAOI and RLM

do not endorse sites behind external links.

Read more articles and essays concerning this institutional

source by visiting the sub-index page for the Frist

Center for the Visual Arts in Resource

Library Magazine.

Visit the Table

of Contents for Resource Library Magazine for

thousands of articles and essays on American art, calendars, and much more.

Copyright 2003, 2004 Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc., an Arizona nonprofit corporation. All rights

reserved.

sweeping social, artistic,

and political transformations that took place during two of the most critical

decades in American history. Featuring approximately 60 paintings, Coming

Home includes works by such acclaimed painters as Regionalists Thomas

Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry; Magic Realist Paul Cadmus; Surrealist

Federico Castellon; and Social Realists Ben Shahn and Raphael Soyer. The

time period of the exhibition extends from the Wall Street Crash of 1929

and proceeds through the years of the Great Depression, concluding with

images showing the impact of World War II on the home front. (right:

Thomas Hart Benton, Fisherman at Sunset, 1947, gouache on

paper, 15 x 21 inches)

sweeping social, artistic,

and political transformations that took place during two of the most critical

decades in American history. Featuring approximately 60 paintings, Coming

Home includes works by such acclaimed painters as Regionalists Thomas

Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry; Magic Realist Paul Cadmus; Surrealist

Federico Castellon; and Social Realists Ben Shahn and Raphael Soyer. The

time period of the exhibition extends from the Wall Street Crash of 1929

and proceeds through the years of the Great Depression, concluding with

images showing the impact of World War II on the home front. (right:

Thomas Hart Benton, Fisherman at Sunset, 1947, gouache on

paper, 15 x 21 inches) of New York by Isaac Soyer, Joseph Hirsch, and Eugenie

MacEvoy, and then continues with depictions of steamy Southern nights by

Charles Shannon and William Hollingsworth; Midwestern farms and farmers

by Guy MacCoy and John Steuart Curry; and people living and working in the

inhospitable environments of Western deserts and mountains, as shown in

paintings by Peter Hurd and Alfredo Ramos Martinez. (right: Louis

Freund, Transcontinental Bus, 1936, oil on panel, 25 x 31 inches)

of New York by Isaac Soyer, Joseph Hirsch, and Eugenie

MacEvoy, and then continues with depictions of steamy Southern nights by

Charles Shannon and William Hollingsworth; Midwestern farms and farmers

by Guy MacCoy and John Steuart Curry; and people living and working in the

inhospitable environments of Western deserts and mountains, as shown in

paintings by Peter Hurd and Alfredo Ramos Martinez. (right: Louis

Freund, Transcontinental Bus, 1936, oil on panel, 25 x 31 inches)